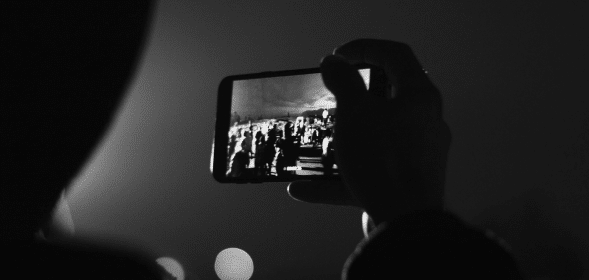

Can You Record the Police?

The First Amendment protects your right to record police engaged in official duties. Recording the police can offer perspective, ensure police accountability, and provide critical evidence in police brutality cases. However, there are limits on when, where, and how you can record them. Knowing your rights and how to best exercise them is important. If you have been harassed by the police for recording an interaction, it may be smart to speak with a civil rights attorney about your potential legal options.

Were you or a loved one a victim of police brutality?

Attorneys that work with Police Brutality Center may be able to assist you.

"*" indicates required fields

Content Last Updated: March 13, 2025

In the age of smartphones and growing concerns about police brutality, it’s not uncommon for people to photograph, film, and record police officers on duty in hopes of catching illegal behavior in the act. In recent years, bystander recordings have been instrumental in holding officers accountable for acts of police brutality, excessive force, and killings caught on video.

Despite what an officer might tell you, it is generally legal to record the police.

However, there are limits to when, where, and how you can record. It’s important to understand your rights, know when you have the power to record the police, and be able to exercise that right safely.

It really just depends upon the jurisdiction. So for example, in New York, you can and probably should record the police if it’s in situation where you’re concerned about the conduct and potentially your safety. But there are jurisdictions where you may not have the ability to record the police. So it’s really dependent upon where you are. There are certain statutes that protect the recordings that you make. In New York, you have the right to record act and that evidence of what’s obtained from the recording could be used in a case. So it is important if you do have some means of recording an interaction with the police to do so. If you’re concerned about what may take place.

Can You Record the Police Under the First Amendment?

Yes, the First Amendment offers many protections, including the freedom of speech and the press. Courts have held that filming the police—under the right circumstances—is protected activity under the First Amendment.

Recording the police has been broadly defined as news and information gathering that’s protected free speech. While the Supreme Court hasn’t ruled on the issue specifically, it has explained that there is a “paramount public interest in a free flow of information to the people concerning public officials.”

In other words, the Supreme Court recognizes it is important to be transparent about the conduct of officers who serve the public. If this transparency is aided by recording officers engaged in potentially unlawful and harmful behavior, that activity should be protected.

While the Supreme Court hasn’t addressed the matter, other federal courts have. Recording the police has been recognized as a protected right under the First Amendment by the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 10th, and 11th U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals.

In a recent decision by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the court concluded that the “right to film the police falls squarely within the First Amendment’s core purposes to protect free and robust discussion of public affairs, hold government officials accountable, and check abuse of power.”

Is it Ever Illegal to Record the Police?

Just because you have the right to record the police doesn’t mean the right is unlimited. Similar to other Constitutional protections, there are carveouts and limitations on when and how those rights can be exercised.

Generally speaking, the right to record the police is limited to situations when the police officer is acting in their official capacity, and recording does not interfere with the officer’s lawful duties, create a safety hazard, or violate another law.

Here’s a breakdown of when it could be illegal to record a police officer:

Recording Would Cause a Safety Risk

It’s okay to record the police unless doing so would put yourself, another bystander, or the police officer in danger.

When might it be unsafe to record a police officer? Often, it depends on how close you are to the encounter. Being too close could put you in danger and interfere with the officer’s ability to do their job safely.

Some states have begun to limit how close you can be to a police officer actively engaged in official duties. For instance, Indiana has a new law that allows officers to order bystanders to maintain at least 25 feet between themselves and officers during investigations. Maintaining this distance can be important for safety and ensuring that a crime scene is not disturbed.

Recording an officer might also create a safety risk if the person being searched or arrested by the officer is unhappy about being filmed. They might become aggressive and violent, which could create a dangerous situation for you, other bystanders, and the officer.

Recording on Private Property

You cannot trespass or violate another person’s expectation of privacy to record a police officer. Your right to film is only protected when you have the owner’s consent to be on the premises.

If the premises owner asks you not to film, you can no longer continue to record the police interaction.

Recording Violates State Wiretapping Laws

States have wiretapping laws that may prohibit or restrict the ability to record video or audio footage.

Currently, 38 states and Washington D.C. have “one party” consent laws. Simply put, one party to the conversation must consent to being recorded. The remaining 12 states require the consent of both parties—meaning that recording an officer privately could destroy the evidentiary value of the footage you capture.

However, courts have held that privacy and wiretapping laws don’t apply to recording the police. Why? Police officers don’t have a reasonable expectation of privacy while on duty. They are, after all, serving the public. The public has a direct interest in preserving transparency in police conduct. Since recording the police in certain situations can promote transparency, it follows that privacy and wiretapping laws should not apply.

Some states, including Hawaii, have gone a step further and passed laws protecting the right to discreetly record the police. These laws help ensure police officers don’t alter their conduct because they know they’re being filmed. As a result, the recordings capture the officer’s true colors.

Ultimately, however, the best course of action in most states will involve recording a police officer out in the open—making it obvious that they’re being filmed.

Interfering With a Police Officer’s Duties

You cannot record the police if you are actively interfering with their ability to do their job.

Courts may believe that you’re interfering with a police officer’s duties if you:

- Speak with witnesses or suspects

- Physically restrain the officer

- Put yourself between the officer and the suspect

- Disturb evidence or the scene of the police encounter

If you interfere with a police officer’s official duties, you may face criminal charges for disorderly conduct, obstruction, or other similar crimes.

You can reduce the risk of charges by maintaining a safe distance between you and the officer, recording out in the open, and remaining silent.

Breaking the Law

Your right to record the police does not extend to situations where you violate the law.

Failing to Comply With an Officer’s Orders

There are times when a police officer might instruct you to back away or leave the scene. You could be breaking the law by refusing to comply if there’s a legitimate reason for these requests.

Trespassing

As mentioned previously, you cannot enter someone else’s premises without their consent to record to the police. You could face criminal trespassing charges if you enter the property or refuse to leave when the owner asks.

Stalking

It can be your right to record a police officer on duty in public. However, the right does not extend to filming officers in private, especially when they are off duty. In these situations, your conduct might be considered stalking or harassment, depending on the laws of your state.

Why Should You Film the Police?

So, you have the right to film the police under the First Amendment. But why should you?

It’s simple: accountability.

When you record the police, you capture their official conduct on film. If the police officer does something illegal, they’ll have a hard time talking their way out of it, lying, or casting blame.

Research suggests that video footage often contradicts what police write in their reports. In fact, out of 10,000 nonfederal officers arrested for various charges, more than 6 percent had made false statements or reports.

When police lie in subsequent reports about what went down during a search or arrest, your video footage can prove their accounts wrong and, ultimately, hold them accountable.

Police officers are figures of authority. We put our trust in them every day. In return, we expect they will uphold the law and be models of how law-abiding citizens should act. When police believe they’re above the law or get caught up in the badge, video recordings of their unlawful or downright heinous acts can be incredibly helpful in changing the system and getting justice for those harmed.

You may also want to record the police because, despite a growing number of police departments implementing body cameras, many officers don’t always wear or use them properly. Additionally, the footage isn’t always available to the public.

By recording the police yourself, you ensure that important—and potentially volatile—interactions are recorded.

Do Police Officers Always Wear Body Cameras?

Currently, 25 states and the District of Columbia have laws on the books that require funding for police body camera programs or mandate the use of the equipment statewide. Another six states—Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Tennessee—are considering similar legislation.

Under these laws, police officers must generally wear and use their body cameras while on duty and interacting with the public. Officers must provide a compelling reason for failing to comply with the law.

These mandates aren’t surprising, given that 92 percent of people surveyed support equipping police with body cams, and more than half said they’d pay higher taxes to fund body cam programs.

Some law enforcement agencies, particularly those in large cities, require their officers to wear body cameras even without state mandates. In 2018, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that about 48 percent of law enforcement agencies nationwide had purchased body camera equipment.

Research suggests that body cameras have a positive impact on policing. One study found that after body cam programs rolled out, complaints against the police dropped by 90 percent, while reports of excessive force dropped by 50 percent.

However, are police officers actually complying with these laws and department mandates?

While there aren’t hard and fast statistics on how often police use their body cameras, it is known that police will turn them off when given a choice. The Mesa, Arizona, police department found a 42 percent decrease in recording when officers were given complete control over how and when to utilize their body cams.

How Can I Safely Record the Police?

Police officers won’t always be happy that you’re exercising your First Amendment right to record them. Recording can also be dangerous, especially if the officer is engaged in a particularly hostile interaction with a suspect.

Here’s how to record the police safely and ensure you’re staying within the limits of the law:

- Maintain a safe distance from the officer to ensure they have space to do their job safely.

- Do not engage with the officer or anyone with whom they are interacting.

- Keep your smartphone out in the open to make it obvious you’re recording. If you try to conceal your phone, the officer could mistake it for a weapon, and the situation may escalate.

- Keep your hands visible at all times. If necessary, use voice commands to control your phone and the recording.

- Keep a steady hand and ensure the camera captures the action and surrounding scene.

Ultimately, you want to capture the officer’s conduct without escalating the situation or putting yourself or others in harm’s way. Try to remain calm and, if asked to stop, explain that you are exercising your Constitutional right to free speech.

Can The Police Delete My Photos or Videos?

Legally, no. However, the police may try to use their authority to bully you into erasing the videos or photos you’ve taken. You do not have to give in to these commands.

The police cannot simply grab your phone and delete the recordings themselves. Such actions would be a blatant violation of your Fourth Amendment rights.

They may have the authority to temporarily seize and search your phone after securing a search warrant. Even in these instances, however, it would be illegal for the police to alter or delete any of the files on your smartphone.

You can protect your recordings by ensuring they’re backed up on the device and uploaded to the cloud. Even if the original files are deleted or altered on your phone, a digital copy will be available for download on other devices.

What Should I Do If I’m Detained By the Police While Recording?

Whether you’re recording the police as a bystander or as a suspect, it’s possible you may be detained after your interaction.

Being detained is different than being arrested. The police have the right to detain you for a short period—usually no more than two hours—if they have a reasonable suspicion that you’ve committed a crime. While detained, it’s possible that you’ll be handcuffed or patted down. However, you should not be transported to the police station.

If you’re detained, don’t resist. Resisting in these situations can do more harm than good. You’ll be asked questions. The best course of action involves providing your name and other basic identifying information. Decline to answer other questions.

Ask if you are free to go. Remember, the police cannot detain you without reasonable suspicion that you’ve committed a crime. If you’ve maintained a safe distance while recording, followed the officer’s instructions to move back, and recorded their actions lawfully, they may have to release you.

If told you’re not free to go, tell the officer you’re invoking your right to remain silent and ask to speak with an attorney.

It can be important to speak with an attorney after an encounter with the police, especially if you’ve recorded them engaging in excessive force or abusing the power of their badge. Your attorney can help you protect your rights, get the recording into the right hands, and potentially hold the officer accountable for their abusive actions and your unlawful detention.