What Is the Civil Rights Movement?

Were you or a loved one a victim of police brutality?

Attorneys that work with Police Brutality Center may be able to assist you.

"*" indicates required fields

Content Last Updated: July 10, 2024

The civil rights movement took place in the 1950s and 1960s and was an effort by Black Americans to gain equal protection and rights under the law. The Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation in the middle of the 19th century ended slavery in an official capacity. Still, discrimination against Black people continued for decades throughout American history, particularly throughout the southern United States.

The efforts of many prominent Black Americans and their white allies came to a head in the 1950s and 1960s when landmark legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, passed and activists such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., John Lewis, and Malcolm X came to prominence.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and other influential organizations were also formed at this time. Concepts of Black power and community developed and strengthened.

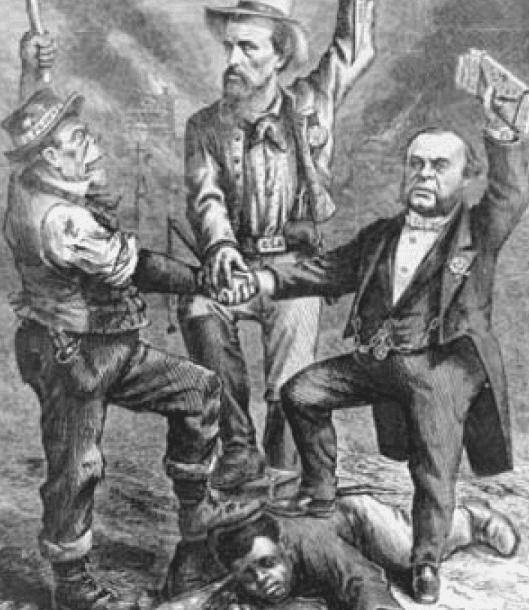

To understand the civil rights movement of the 1960s, one must examine the struggle of Black Americans immediately following the end of the Civil War, during an era known as Reconstruction.

Post-Civil War American & Reconstruction

The 14th Amendment to the Constitution granted Black people equal protection under the law, and the 15th Amendment to the Constitution gave Black men the right to vote. Unfortunately, many white Americans weren’t comfortable with the rights their former slaves had gained and began pushing for laws that would marginalize the Black community.

These laws were known as “Jim Crow” laws, and they restricted access to public facilities. Notable examples include segregated schools and separate bathroom facilities, which were common in the southern states. Laws forbade interracial marriage, which would remain illegal well into the 20th century. Voting literacy tests made it difficult for Black voters to exercise their right to vote because of high illiteracy rates.

Jim Crow laws weren’t as common in the northern states, but discrimination wasn’t something experienced solely by Black citizens in the American South. Efforts by inhospitable white northerners made it difficult for Black Americans to buy a house and attend school. Some northern states even passed laws limiting voting rights.

The landmark Plessy v. Ferguson case of the late 1890s cemented efforts to segregate Black Americans from whites by introducing the flawed concept of “separate but equal” under the law. The case stemmed from a Black American’s assertion that his Constitutional rights were violated when he was asked to exit a “whites only” train car.

The Black Experience in Pre-World War II America

Black people commonly found work as farmers, servants, and factory workers in the early half of the 20th century. While their white peers had the opportunity to earn higher wages due to the manufacturing boom of the WWII economy, Black people weren’t offered well-paying jobs due to racial discrimination. It was also difficult for Black people to join the military.

A change would come in 1941 when the threat of a march on Washington convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue an executive order that prevented employers from denying Americans jobs based on race, color, creed, and national origin.

Despite enduring racial segregation and discrimination throughout World War II, Black Americans served in the war with distinction. Aviators from the famed Tuskegee Airmen returned after the war to be granted an overwhelming number of Distinguished Flying Crosses. Unfortunately, they and other Black war heroes would continue to experience discrimination at home.

In 1948, President Harry Truman signed an executive order meant to end discrimination in the military. The order was part of a civil rights agenda his administration initiated during his presidency. After the war, these and other events would influence the burgeoning civil rights movement that would gain incredible momentum in the next decade.

Separate But Equal Becomes a Flashpoint for the Civil Rights Movement

The concept of separate but equal began in the 1890s with a fight over train cars separated by race and would reach a boiling point in 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white person on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

After police arrested Mrs. Parks, Black citizens in Montgomery formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), which would give a local minister the opportunity to rise to national prominence in the civil rights movement. That minister’s name was Martin Luther King, Jr., and he would become the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

Soon after Mrs. Parks’ arrest, the MIA would stage the now-famous Montgomery bus boycott, which would last more than a year. The boycott led to a Supreme Court ruling in 1956 that declared segregated seating unconstitutional.

Desegregating the Nation's Public School System

Another historic event that would propel the civil rights movement forward was the Brown v. Board of Education case, which took on segregation in public schools. In 1954, the United States Supreme Court made it illegal to segregate public schools.

A few years later, a group of Black students who would eventually become known as the Little Rock Nine arrived at Central High School in Arkansas to begin classes, but the state’s governor, Orval Faubus, sent the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students from entering the school.

Nearly a month later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to escort the students to their classes amid a screaming, angry mob of white students. Unfortunately, the Little Rock Nine experienced harassment and prejudice throughout the school year despite the Supreme Court’s decision that segregated schools were unconstitutional.

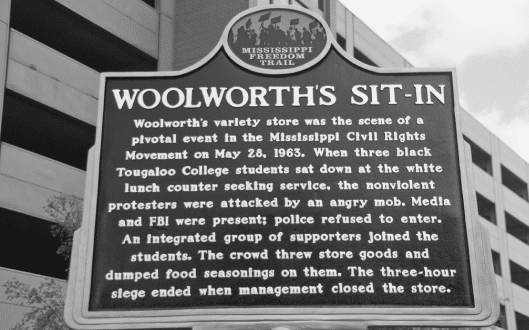

The Woolworth's Lunch-Counter Protest

Another major event in the saga of civil rights in the United States occurred in 1960 with the Woolworth’s lunch-counter incident. In Greensboro, North Carolina, a small group of college students refused to leave the lunch counter until wait staff served them. Their efforts led to the Greensboro sit-ins, where police often arrested protesters for their actions.

Hundreds of people joined the protests and began boycotting the lunch counters until the owners eventually agreed to serve the original four students. One of the remarkable facets of the sit-in was that they were peaceful demonstrations of civil disobedience that led to the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The group encouraged college students to get involved with the civil rights movement.

The Freedom Rides Galvanize the Nation

Unfortunately, not all civil rights protests were free from violence. In 1961, a group of Black and white activists boarded a bus in Washington, D.C., to test whether the Supreme Court decision declaring segregation of interstate transportation unconstitutional would hold up in real-life practice.

Throughout the group’s journey, they experienced violence from police officers and protesters, with a culmination of events occurring in May of 1961 when an armed mob threw a bomb onto the bus.

The group was able to escape the bombing but were unable to continue their journey until they received help from U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who enlisted a driver and a police escort. When a group of Freedom Riders reached Jackson, Mississippi, in late May 1964, police arrested them for trespassing in a facility labeled as whites only. The NAACP brought the issue to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed the convictions.

The number of Freedom Riders would grow for months after the violent incidents until the Interstate Commerce Commission issued a statement declaring that segregation was illegal on interstate buses and transit terminals.

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The violent clashes and peaceful demonstrations of the latter half of the 1950s and the early 1960s eventually led to a landmark nonviolent protest in 1963 known as the March on Washington. Leaders including Martin Luther King, Jr. and A. Philip Randolph attended the human rights event and made famous speeches. It was at this event that King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Major Legislation of the Civil Rights Era

The first significant piece of legislation signed into law as a result of the civil rights movement was the Civil Rights Act of 1957. President Eisenhower signed the law and made it a crime to prevent someone from exercising their right to vote. The law also created a government department that would investigate voter fraud.

In 1964, another piece of legislation passed through Congress: The Civil Rights Act of 1964. Signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the legislation was initially set for passage during President John F. Kennedy’s tenure, but he died from an assassin’s bullet before he could sign it.

Rights offered by the act included:

- Equal employment protections

- Limitations on the use of voter literacy tests

- Authorization for the authorities of the federal government to maintain the desegregation of public facilities

The government didn’t stop with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, however. President Johnson signed another piece of legislation in 1965 called the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which expanded upon the protections granted by the Civil Rights Act. The government banned all voting literacy tests, and the act gave the country’s attorney general the power to contest local poll taxes.

A lawsuit known as Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections brought as a result of the Voting Rights Act led to the final declaration that poll taxes were unconstitutional.

Violence in the Fight for Civil Rights

A peaceful demonstration turned particularly violent in 1965 when marchers traveled from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest the murder of activist Jimmie Lee Jackson by a white police officer. As the group marched toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were met by a group of police sent by the state’s governor, George C. Wallace.

Wallace was a well-known opponent of desegregation, and his police force threw teargas and beat protesters who refused to stop the march. Many people were hospitalized, and history would eventually call the incident Bloody Sunday. Further demonstrations may have spiraled out of control, but Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders pushed to keep the protests peaceful and nonviolent despite the violence enacted against the protesters by police.

Another violent event in 1965 occurred during a rally at the Audubon Ballroom in New York City when assassins killed civil rights activist Malcolm X in front of his pregnant wife and four daughters. Malcolm had recently founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity and had already survived an assassination attempt earlier that year.

The most famous event to occur during the civil rights movement happened in 1968 when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated while standing on his hotel room balcony. Riots and looting followed his death, which pushed President Johnson to pass additional laws to protect the civil rights of all Americans.

Most notably, President Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law in April of 1968, just a few days after King’s assassination. The law aimed to prevent housing discrimination based on race, sex, religion, and national origin. The Fair Housing Act was the last significant piece of civil rights legislation passed by Congress during the remarkable era.